sustaining

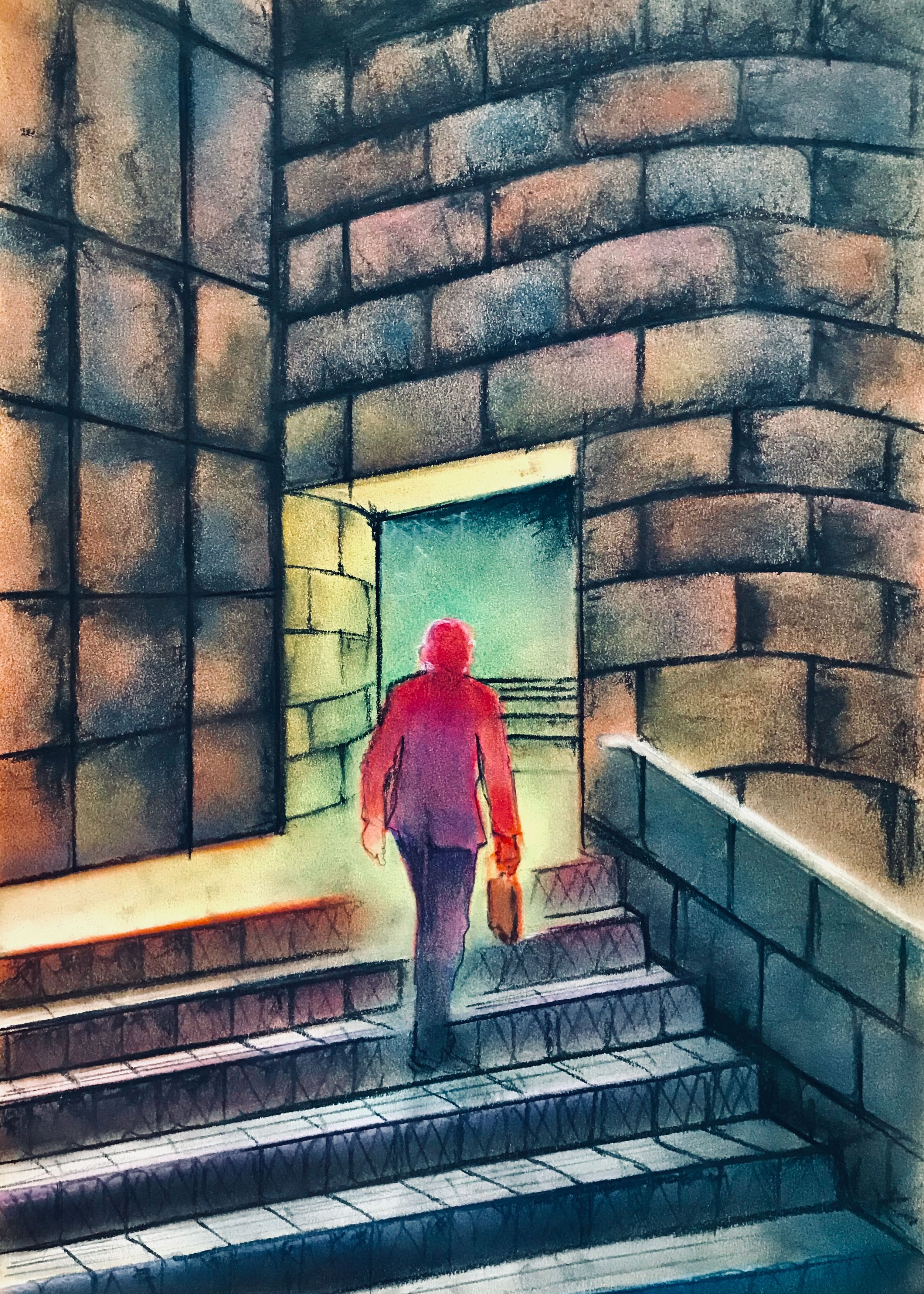

The Secret

the world is packed with

billions of people whose lives

and deaths are useless and

when one of these jumps up

and the light of history shines

upon them, forget it, it's not what it seems,

it's just another act to fool the fools again.

Charles Bukowski

The fifth and final phase in a quest for growth is sustaining the change and investing in institutionalization

-

In 2008-09 the Ford Motor Co. embarked on one of the most courageous journey's in corporate history. Instead of seeking a bailout from the US government following the 2008 financial crisis when it was just months away from running out of cash, Ford managed to reduce its debt from $37 billion in 2008-09 to $14 billion in 2012-13. This while the other two Detroit-based car makers General Motors Co. and Chrysler Group Llc opted for government help.

A key decision was to bring Alan Mulally, a complete outsider who had become known for the turnaround at Boeing, as CEO. Before Mulally, Ford was known for infighting, back-stabbing and a lack of accountability—a culture that had seeped into the company. Besides, it had also got itself a reputation as a car maker with a lacklustre product line up. With single-minded vision, Mulally managed to convince his senior leadership about the mission to save Ford, giving employees belief in their company. Mulally, who found “unbelievable inspiration in Henry Ford", decided to focus on the core business and divest brands such as Jaguar, Land Rover, Aston Martin and Volvo. These brands had been trophy acquisitions by the previous management and their divestment was widely considered as one of the primary reasons for Ford’s revival.

By adopting a “One Ford, One vision" strategy, the company chose to make cars that would have similar parameters in quality, fuel efficiency and design, irrespective of the different markets that they would cater to. Alan Mulally talked incessantly about his “One Ford” turnaround plan. He had it distributed to every employee on a wallet-sized card. Crucial to the turnaround was the Thursday review of One Ford. At these meetings, all aspects of the business ranging from engineering plans to a look at the balance sheet and covering all geographies from India to North and South America were reviewed. Any underperforming area would be dealt with quickly. Bryce Hoffman, the author of a book on Mulally’s time at Ford, wrote, “After six months, those of us who followed the company had gotten sick of hearing about [it].” When in one interview Hoffman asked Mulally if he’d be sharing something new, the CEO was couldn't believe the question: “We’re still working on this plan,” he replied. “Until we achieve these goals, why would we need another one?” That relentlessness paid off. In less than four years Mulally pulled Ford back from the brink of bankruptcy and made it one of the most profitable automakers in the world.

In an interview Mulally said that he spent 25-30% of his time on succession and leadership planning. “The people who are leading Ford now have to believe that they don’t want to go backward. They don’t want a different plan. They know their working together is the absolute key," he said.

In the twentieth century, many organizations followed the model of being a “machine,” where predictability, stability, and hierarchy were the norm. This model was very good at delivering predictable performance but poor at coping with disruption. Many organizations still live with this legacy approach while their stakeholders demand something very different: a more “organic” organization where continual transformational is the norm. Enabling transformation requires giving organizational members the information and resources they need to develop and innovate in other directions. Executives who have led successful transformations commonly describe how knowledge and resource sharing allowed employees to develop in this way, which enabled the organization to move toward a state of continual transformation. Increasingly, managers and leaders are expected to deliver continual, rather than episodic, transformation and evolution. Transitioning to this state requires not only new leadership skills, organizational structures, processes, and KPIs, but also bringing all these things together to operate within this new paradigm.

Sustain the Change: In the final phase, resources and leader focus are maintained to uphold momentum. Continuous communication through various channels ensures stakeholder engagement and progress.

Monitor and Adapt: Middle management and teams oversee change projects, adjusting plans as needed. New teams aid in system restructuring, with activities shared among stakeholders.

Institutionalize Change: Demonstrating improvements and aligning behavior with the vision, quantifying results, and involving all levels of management ensures sustained success. Board involvement supports management succession planning.

“When your company is doing well, and money is pouring in, how do you know if it could be doing better? How can you tell which management practices are making the difference—and which are merely not doing obvious harm?

A massive benchmarking study comparing nine pairs of European companies over 50 years, in which each pair was from the same industry (and, preferably, the same country) and included one exceptional performer and one less impressive, but solid performer yielded four main findings - called the four principles of enduring success:

1. Exploit before you explore - Great companies don’t innovate their way to growth—they grow by efficiently exploiting the fullest potential of existing innovations.

2. Diversify your business portfolio - Good companies, conscious of the dangers of irrational conglomeration, tend to stick to their knitting. But the great companies know when to diversify, and they remain resilient by maintaining a wide range of suppliers and a broad base of customers.

3. Remember your mistakes - Good companies tell stories of success, but great companies also tell stories of past failures to avoid repeating them.

4. Be conservative about change - Great companies very seldom make radical changes—and take great care in their planning and implementation.

How much difference do these principles make? An investment of $1 in 1953 in the group of companies in the study that consistently applied them—insurers Allianz, Legal & General, and Munich Re; financial services firm HSBC; building materials maker Lafarge; high-tech firms Nokia and Siemens; oil giant Shell; and pharmaceutical firm GlaxoSmithKline—would be worth $4,077 today. A $1 investment in the comparison companies—Aachener und Münchener, Prudential Limited, and Cologne Re; Standard Chartered; Ciments Français; Ericsson and AEG; BP; and Wellcome—would have yielded $713.”