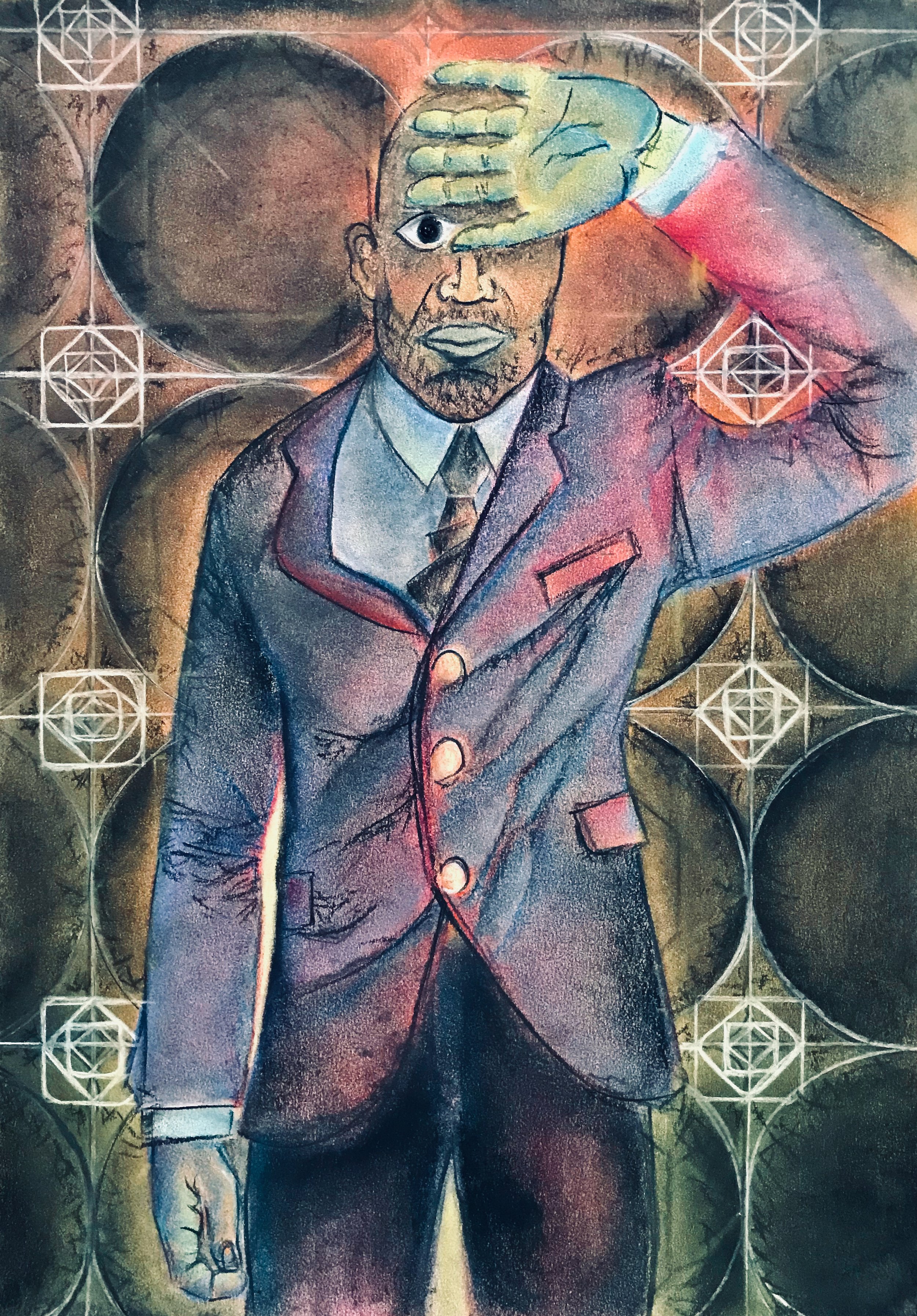

Design reflects truth

Dark Night of the Soul

And in the luck of night

In secret places where no other spied

I went without my sight

Without a light to guide

Except the heart that lit me from inside.

St. John of the Cross

-

India’s Infosys had developed a widely admired approach to leadership development. However, real trouble reared its ugly head in 2014 and exposed the manner in which it had failed to tie development of leadership capabilities with the transformational needs of the business. The result - the IT giant was forced to turn to an outside CEO to drive necessary changes. And that too didn’t last for long when the newly appointed CEO exited suddenly in 2017. Not only did the company and its stakeholders have to live with the uncertainty of another leadership transition—the fourth in the past 10 years—but they also had to contend with the rapidly increasing hostility between the company’s board and its founders.

The dark side of founders.

In 2014, the Indian software services had seen the end of an era as N.R. Narayana Murthy, the 67-year-old co-founder and executive chairman, announced that after 33 years, he and the other two remaining co-founders — S. Gopalakrishnan, who served as executive vice chairman, and CEO S.D. Shibulal — were stepping down. Furthermore, the new CEO, 47-year-old Vishal Sikka, was not from within the 160,000-strong Infosys talent pool. The move by the founders evoked mixed reactions, ranging from being a masterstroke to absence of any other choice for the founders. What was evident to many were the existing urgent organizational and structural challenges including: stability, sales and marketing, attrition, pricing strategy and responsiveness to customers. By 2017, Indian IT companies were struggling in a rapidly evolving technological environment, and were losing share to multinationals and some newer, nimbler firms that specialized in digital technologies. Challenges at the senior level, including at Infosys, were making navigating the changes in the industry all the more complicated. Market conditions had been the same for all firms in the sector. Experts noted, however, that Infosys’ inability to deal with the changing environment was a direct offshoot of its founder-CEO model. The founders had come with a particular mindset and created processes and systems that had not changed over the past three decades. They had needed to change with the changing times and inject fresh thinking because at different stages of a company’s evolution, different competencies are required. Furthermore, investments made by Infosys in developing leadership (it set up a leadership institute in 2001) appeared to have largely been focused on developing junior and middle management. The investments didn’t seem to have prepared the company for a leadership crisis at senior managerial levels. At the time the problems were being traced back to the history of the organization. Infosys was started in 1981 by seven co-founders led by Murthy. Two of the co-founders left early on, and the third retired in 2011. The rest took turns in the CEO role. Murthy had the longest run — 21 years before voluntarily passing the baton to younger co-founder Nandan Nilekani in 2002. Nilekani, however, only lasted five years as CEO. At Murthy’s behest, he stepped down to make way for Gopalakrishnan. Shibulal subsequently took over in 2011. The same year, Murthy turned 65 and stepped down as non-executive chairman.

Double-standards.

At the time of Murthy’s retirement, Infosys increased the retirement age for chairman from 65 to 70, but with a caveat: The policy would not apply to any of the founders. Then Murthy broke his own rule when he returned in 2013 as executive chairman. The company was floundering and Murthy came back to set it right. In fiscal 2012-2013, Infosys grew at a rate of 6.6% — one of its worst performances since the company’s inception. Its growth forecast of 6% to 10% for the year was lower than the industry projection of 12% to 14%. The company’s margins, once the best in the industry, also slipped.

Murthy also broke another of his well-articulated and publicized values — that his children would not join the company. When he returned to Infosys for his second go-round, Murthy brought on his son, Rohan Murty, as his executive assistant. He also set up a dual power center in the company in the form of the chairman’s office. During Murthy’s second term, the company continued to underperform compared to its peers. More importantly, some of Murthy’s decisions, policies and experiments with the organizational structure resulted in deep employee disengagement. Attrition reached an all-time high, and more than a dozen very senior executives left the company — including the joint-president, head of the Americas division, global sales head, head of delivery, head of strategic sales and head of Infosys’ BPO and India business. Some of those executives had been considered frontrunners for the CEO position.

Faulty elevations.

At the time of the new CEO, Sikka’s, appointment, Infosys promoted the president and also elevated 12 executives to the positions of executive vice president and gave them key responsibilities. This move was largely perceived as a bid to stem further exodus. So while the new CEO did have a senior team in place, it was a relatively unproven one. Worse, Sikka, for all his credentials, did not have any experience as a CEO, at heading sales or even as a profit and loss account owner. While Sikka’s capabilities and his thought process were seen as extremely useful for IT version 3.0, or five years down the line the question was: would he deliver in the short and medium term?

-

GE transplant Bob Nardelli and his leadership at Home Depot post-2000 is one such example of being led astray. Nardelli tried to transform Home Depot by selling supplies to construction professionals as well as to homeowners. The pursuit of customers in adjacent markets distracted attention from Home Depot’s core problem of slumping store sales. Nardelli was credited with doubling the sales of the chain and improving its competitive position. Revenue increased from $45.74 billion in 2000 to $81.51 billion in 2005, while net earnings after tax rose from $2.58 billion to $5.84 billion. During Nardelli's tenure, The Home Depot stock was essentially steady while competitor Lowe's stock doubled, which along with his $240 million compensation eventually earned the ire of investors.

Style did matter.

Nardelli’s blunt, critical and autocratic management style turned off employees and the public. When Nardelli resigned, under intense pressure from shareholders, the strategy was immediately reversed by a longtime deputy to Nardelli at GE and Home Depot, Blake who was said to lack Nardelli's hard edge and instead preferred to make decisions by consensus, and the wholesale arm sold off to allow the company to refocus on its core retail business. From seventh-largest global retailer, Home Depot has since jumped to third. In comparison to Nardelli whose numbers-driven approach never appreciated the role of the store and its associates, Blake's strategy had revolved around reinvigorating the stores and its service culture (engaging employees, making products readily available and exciting to customers, improving the store environment, and dominating the professional contracting business, an area in which Home Depot's closest rivals trail far behind), as he recognized that employee morale is a more sensitive issue in retail compared to other industry sectors like manufacturing. Blake was given credit for returning to the "Orange Apron Cult — the nearly religious zeal for knowledgeable employees and high levels of customer service that was the secret of the company’s original success", as he believed that customer service was the key to Home Depot to differentiate itself from competitors on aspects other than price.

Past does shape the future.

The downturn of 2008 had hit everyone hard, and observers were noticing the distinction between senior executives’ making resource allocation decisions that necessitated painful choices, and making decisions that fundamentally undermined the culture and values of an organization. Home Depot had been one of the business success stories of the previous quarter century. Founded in 1978 in Atlanta, the company grew to more than 1,100 big-box stores by the end of 2000; it reached the $40 billion revenue mark faster than any retailer in history. The company’s success stemmed from several distinctive characteristics, including the warehouse feel of its orange stores, complete with low lighting, cluttered aisles, and sparse signage; a “stack it high, watch it fly” philosophy that reflected a primary focus on sales growth; and extraordinary store manager autonomy, aimed at spurring innovation and allowing managers to act quickly when they sensed a change in local market conditions. Home Depot’s culture, set primarily by the charismatic Marcus (known universally among employees as Bernie), was itself a major factor in the company’s success. It was marked by an entrepreneurial high-spiritedness and a willingness to take risks; a passionate commitment to customers, colleagues, the company, and the community; and an aversion to anything that felt bureaucratic or hierarchical. Longtime Home Depot executives recall the disdain with which store managers used to view directives from headquarters. Because everyone believed that managers should spend their time on the sales floor with customers, company paperwork often ended up buried under piles on someone’s desk, tossed in a wastebasket—or even marked with a company-supplied “B.S.” stamp and sent back to the head office. Such behavior was seen as a sign of the company’s unflinching focus on the customer. “The idea was to challenge senior managers to think about whether what they were sending out to the stores was worth store managers’ time,” says Tom Taylor, who started at Home Depot in 1983 as a parking lot attendant and rose to become executive vice president for merchandising and marketing. There was a downside to this state of affairs, though. Along with arguably low-value corporate paperwork, an important store safety directive might disappear among the unread memos. And while their sense of entitled autonomy might have freed store managers to respond to local market conditions, it paradoxically made the company as a whole less flexible. A regional buyer might agree to give a supplier of, say, garden furniture, prime display space in dozens of stores in exchange for a price discount of 10%—only to have individual store managers ignore the agreement because they thought it was a bad idea. And as the chain mushroomed in size, the lack of strong career development programs was leading Home Depot to run short of the talented store managers on whom its business model depended. Store managers’ autonomy freed them to respond to local conditions, but it made the company as a whole less flexible. All in all, the cultural characteristics that had served the retailer well when it had 200 stores started to undermine it when Lowe’s began to move into Home Depot’s big metropolitan markets from its small-town base in the mid-1990s. Individual autonomy and a focus on sales at any cost eroded profitability, particularly as stores weren’t able to benefit from economies of scale that an organization the size of Home Depot should have enjoyed.

What got us here, won’t get us there.

Nardelli’s arrival at Home Depot came as a shock. No one had expected that Marcus (then chairman) and Blank (then CEO) would be leaving anytime soon. Most employees simply couldn’t picture the company without these father figures. And if there was going to be change at the top of this close-knit organization, in which promotions had nearly always come from within, no one wanted, as Nardelli himself acknowledges, an outsider who would “GE-ize their company and culture.” But the Home Depot board had decided that a seasoned manager with the expertise to drive continued growth needed to be brought in to run what had become a giant business. The first step had been to deal with immediate problems that weren’t readily apparent either to employees or investors. In addition to the shortage of experienced store and district managers and the challenge from Lowe’s, which successfully attracted women shoppers with its brighter stores and a focus on fashionable kitchen, bath, and home-furnishing products, these problems included poor inventory turns, low margins, and weak cash flow.

Nardelli laid out a three-part strategy: enhance the core by improving the profitability of current and future stores in existing markets; extend the business by offering related services such as tool rental and home installation of Home Depot products; and expand the market, both geographically and by serving new kinds of customers, such as big construction contractors. To meet his strategy goals, Nardelli had to build an organization that understood the opportunity in, and the importance of, taking advantage of its growing scale. Some functions, such as purchasing (or merchandising), needed to be centralized to leverage the buying power that a giant company could wield. Previously autonomous functional, regional, and store operations needed to collaborate—merchandising needed to work more closely with store operations, for instance, to avoid conflicts like the one over the placement of garden furniture. This would be aided by making detailed performance data transparent to all the relevant parties simultaneously, so that people could base decisions on shared information. The merits of the current store environment needed to be reevaluated; its lack of signage and haphazard layout made increasingly less sense for time-pressed shoppers. And a new emphasis needed to be placed on employee training, not only to bolster the managerial ranks but also to transform orange-aproned sales associates from cheerful greeters into knowledgeable advisers who could help customers solve their home improvement problems. As Nardelli likes to say, “What so effectively got Home Depot from zero to $50 billion in sales wasn’t going to get it to the next $50 billion.” This new strategy would require a careful renovation of Home Depot’s strong culture. Imagine the challenge: Clearly, you wanted to build on the best aspects of the existing culture, particularly people’s unusually passionate commitment to the customer and to the company. But you wanted them to rely primarily on data, not on intuition, to assess business and marketplace conditions. And you wanted people to coordinate their efforts, anathema to many in Home Depot’s entrepreneurial environment. You wanted people to be accountable for meeting companywide financial and other targets, not contemptuous of them. You wanted people to deliver not just sales growth but also other components of business performance that drive profitability.

Culture eats strategy for breakfast.

Resistance to the changes was fierce, particularly from managers: Much of the top executive team left during Nardelli’s first year. But some saw merit in the approach and in fact tried to persuade distraught colleagues to give the new ideas a chance. Over time, attitudes slowly began to change. Some of this resulted from Nardelli’s successful efforts to get people to see for themselves why the strategy made sense. But other, more concrete tools, designed to ingrain the new culture into the organization, ultimately prompted employees to pick up a hammer and paintbrush and join the renovation project.

In all of this Mr. Nardelli didn’t seem to have a passion for the heart and soul of Home Depot. While he clearly made interventions that were absolutely necessary, ranging from establishing a more rigorous strategy process to bringing the company’s IT infrastructure up to state-of-the-art standards, he seemed to overlook what made Home Depot a cherished partner to the do-it-yourselfers and contractors who formed the core of its customer base. The original Home Depot strategy depended on extremely knowledgeable service staff who would go that extra mile for customers and who could really help them understand how to accomplish their own goals. In the name of efficiency, Nardelli cut coverage, replaced quite a number of the experienced old-timers with part-timers, and put the whole organization on a tight, numbers-driven, almost military program. Again, many of his changes were for the better – yet the cultural, network, and experience losses eventually caught up with the company and Nardelli was replaced.

-

In 2009, A Lars Olofsson had arrived at Carrefour, a retailing giant, much like a manager joining a football club owned by an impatient and demanding billionaire. Olofsson’s predecessor was an Iberian young gun called Jose Luis Duran, who had been given just three years to turn around the ailing French hypermarket giant before he was given the boot. "We face daunting challenges and it's time for us to confront these challenges if we want to regain our leadership position and conquer, or re-conquer, the hearts of all our customers," Mr Olofsson said at his first presentation to industry analysts and investors as the French hypermarket chain's chief executive.

Easier said than done.

Carrefour's biggest shareholders had become tired of Duran's slow progress and went searching for new management at Europe's big retail and consumer goods companies, eventually hiring one of Nestle's star strategists, Mr Olofsson, a Swedish national. He came from a trio of management talent at Nestle, who were all tipped as possible contenders for the top job at the Swiss food conglomerate. Of the two others, Paul Bulcke became the chief executive at Nestle, and Paul Polman took the top job at another multinational, Unilever. With all eyes on Mr Olofsson, his early performance had to be spot on because Bernard Arnault, Europe's richest person and the boss of the luxury goods group, LVMH, kept a close eye on his investment in Carrefour. Arnault and Colony Capital, a property-investment company, jointly own 14 per cent of Carrefour's shares and 20 per cent of its voting rights, predominantly through a vehicle called Blue Capital. Having bought into Carrefour at the height of the market in 2007 and paid €50 per share, Blue Capital was sitting on massive paper losses. The shares traded at €19.50 and Blue Capital was trying its utmost to help management improve the price. So Mr Olofsson, 59, had to manage the expectations of some powerful owners. In a bid to prove he was "the special one", Mr Olofsson started his role at Carrefour in 2009 with talk about change and embarking on a transformational strategy.

In over their heads.

Industry insiders described him as open and honest, with enough charisma to take on the high-profile role. “The most important objective that we still have,” Lars Olofsson, the incoming Carrefour CEO, told the business world when outlining his planned transformation of the company in June 2009, “is still to become the preferred retailer and this is going to be the primary objective.” Olofsson had been quick to stress that his immediate priority was managing the present while preparing for the future. As CEO, Olofsson was aware that the road ahead was not be easy. He knew that the challenges he and the company faced were not to be underestimated, especially if Carrefour had to overtake Wal-Mart and eclipse Tesco. It was no secret, for example, that Carrefour’s French hypermarket performance was down and the company was struggling to record growth in the domestic market. Modern consumer trends were not favoring the hypermarket format, especially with regard to non-food items. A feature of the contemporary French consumer landscape had led shoppers to seek out specialist outlets, and Carrefour hemorrhaging business. Olofsson also had to address the problems facing the group’s deep discounters. In addition it was not lost on the CEO that the company was experiencing downturn in key European markets. Carrefour, however, had been confident they had their man. “Lars Olofsson has exceptional expertise in consumer markets” Amaury de Seze, Chairman of Carrefour’s board of directors, said of the group’s CEO. “His strong leadership and sales and marketing expertise make him an ideal leader for Carrefour to carry out the next stage of the group’s development.”

Ungrounded ambition.

Going on to say that for the transformation of the company to be successful, and to avoid too much disruption, Olofsson had decided on a restructuring process with a three year time-frame. “Changing the way we are organizing ourselves. Changing the way we are working in our operations and in that sense being able to create margins for future growth and margins for profit enhancements,” he would tell his audience. He launched an ambitious transformation plan for the retail giant based on seven strategic initiatives, including enhanced innovation, customer engagement, agility, and global expansion. The result was confusion, a loss of domestic market share, and a 53% plunge in share price in one year. Olofsson lasted barely two years in the job. Like fans tired of the constant unsettled nature of their football team, analysts had become weary of false dawns and few had been confident in Mr Olofsson's ability to make revolutionary changes and please the demanding owners. "There have been so many unsuccessful attempts to revamp the business in the last 10 years," said Andrew Porteous, an analyst at Evolution Securities. "While Carrefour plan to implement a turnaround plan, the risk of this being unsuccessful is high." Thomas Barrack, billionaire founder of Colony Capital, the California-based investment house and an influential investor in Carrefour since 2007, spoke from the heart when he compared the task of turning round the French group to moving an aircraft carrier.

Hidden incompetency.

Olofsson’s replacement in 2012, Georges Plassat, panned the leadership capability of the previous team, labeling the members “incompetent in mass retailing.” A few weeks after joining, at the annual general meeting, he had likened Carrefour to a chicken that had lost its head. It was a blunt call for change, delivered in inimitable Plassat style. Mr Plassat, 64, was one of the retail world’s most experienced and independent-minded executives. His ambition was to transform Carrefour’s corporate culture, deployment of financial resources and public image. In June 2012, Plassat quickly reconsidered the group's strategy in France and internationally and obtained excellent results with growth. Given the depths to which Carrefour had sunk, progress would take time – like hauling up a galleon from the seabed. In a successful recovery plan, Plassat first focused on shedding operations in noncore markets and streamlining internal operations. He then reignited domestic sales by cutting prices and diversifying stores. He notably decided to give store managers the power to adapt to local tastes.Three years later Carrefour had regained a clear lead in the French market.

Face reality as it is, not as it was or as you wish it to be.

Jack Welch

Many transformation efforts are set up to fail at the quest stage. Under pressure top teams get sidetracked or overreach when they lose focus on what value is worth pursuing—or they take on more change than they can handle. Taking a cold, hard look at the organization and themselves is the first step in getting started. And that means that knowledge, competencies, or activities that had been central to the organization could now present themselves as core rigidities. Because excelling along a set technical trajectory in the past drove the firm to invest heavily to build the capabilities required, these capabilities become deeply rooted in the organization’s routines, and in its culture. In the face of change, however, market leaders sometimes find such historical capabilities ill suited to new conditions. Core competencies could begin to look like core rigidities. And if so, they need to be adapted or jettisoned. The more radical the transformation, the greater the chance that this dynamic will surface. Confronting harsh reality can also involve identifying and addressing blind spots. Investigations of failed efforts reveal three common failings:

Not making a choice- Companies that fail to define a specific quest - a mobilizing theme, find that their efforts towards value creation and leadership development have become ends in themselves—generic efforts, disconnected from the strategy. In other words, without having the right thing to dig their teeth into, companies falter in their journey to growth.

Making the wrong choice - The company, including the board and the top team, get seduced by the vision of an assertive CEO, attempt to imitate the strategic moves of competitors, or fall for recommendations from consultants who are biased and favor particular quests. In such situations, the chosen quest comes to nothing because it did not emerge out of a deep dialogue or shared conviction, or it failed to address the core issues critical to generating value and energizing organizational members.

Making multiple choices - The choice of quest is muddled if leaders can’t agree on which direction to go. Different parts of the business (regions, functions, levels) see different problems and priorities. Thus some companies overreach, taking on too many quests at once or overestimate their leadership capabilities.

“Acceptance is often misunderstood as approval or being against change, but it is neither. Acceptance is about acknowledging the facts and letting go of the time, effort, and energy wasted in the fight against reality. Your reality may be that you are falling behind on revenue, a competitor has outflanked you with a new product, or that the effects of the pandemic are still hurting your business. Whatever it is you’re facing, you can’t employ your best skills to deal with it until you stop the wrangle against reality and accept what you’ve been handed, ready to change things for the better. ”

Whole-making

How wonderful that we have met with a paradox. Now we have some hope of making progress.

Niels Bohr

As companies strive to transform core rigidities and address blind spots so they can redefine the playing field and shape new value proposition, they find that their leaders must also change. Their top people must be able to reimagine the company’s place in the world and transform the organization to live up to a more ambitious purpose. This means a fundamental change not only in the executives themselves but also in how they collectively manage and lead the firm. For instance, a 2022 survey conducted by Strategy&, PwC’s global strategy consulting business, highlighted the importance of balancing certain characteristics that on the surface look paradoxical. We used to accept, for example, that leaders could be either great visionaries or great operators. No longer. Companies now need their top people to perform both roles—to be strategic executors, in other words. They’re also expected to be tech-savvy humanists, high-integrity politicians, humble heroes, globally minded localists, and traditioned innovators. Not only did large majorities of the survey respondents agree on the importance of those roles, but they also voiced alarming concern about leaders’ lack of proficiency in them. Addressing a company’s leadership gaps, however, is not merely a matter of building individual executives’ skills. Although that’s certainly desirable, the need to improve collective leadership is urgent. When senior executives at prominent firms were interviewed to explore the reasons for changed expectations it was clear that to thrive companies need to build new forms of advantage rather than just digitize what they are doing today. Accomplishing that means being ready to shed past belief systems and define new, bolder value propositions. Companies have to switch from competing with rivals to cooperating with partners in networks and ecosystems to create value in ways that no single organization can manage alone. Leaders need to be willing to challenge every aspect of their company: its purpose, its business model, its operating model, its people, and themselves. And conventional ideas about managing have to be inverted. Executives must move away from focusing on their individual areas of responsibility and responding to needs bubbling up from below; instead they must work together as a team to shape the organization’s future and steer a path toward it.

Role-making

There is no 'i' in team but there is in win.

Michael Jordan

Drawing on the experience of others companies it is clear that CEOs must consciously design and build a leadership team that is up to the challenge. This approach has four key components with questions that CEOs can pose to themselves:

Right roles - Every company needs distinct capabilities that allow it to deliver on its purpose, along with leaders who can envision its new place in the world and mobilize it to get there. What roles are needed on the executive team to make that happen?

Right people - Having identified the roles the team needs, we have to think about who will best fill them. Which individuals should be brought together so that the team has the necessary talent and diversity in the C-suite to generate new ideas, challenge traditional thinking, and collaborate on meaningful change?

Right structure - Advancing the company’s agenda means spending energy and time on the big priorities for the future, not just responding to the demands of the organization today. What structures and mechanisms will help you lead the company to its new destination?

Right culture - Building distinctive capabilities require collaboration and commitment to developing a team mentality so that the disparate parts of the organization operate as a harmonious whole. How can trust and a culture that powers the organization’s collective success be built?

Working on them simultaneously is assumed because they reinforce one another. And getting everything right on the first take, including how the team itself is established is not to be fussed over. High-performing leadership teams are not built overnight, nor do they do everything perfectly. Having said all of the above, they are not an excuse for failing to make substantial progress on all four fronts.

“An effective, aligned, and committed executive team — the governance mechanism that shapes the story of an organization unlike any other team — is central to shaping and sustaining impactful corporate purpose.”