founder Leads High-Growth

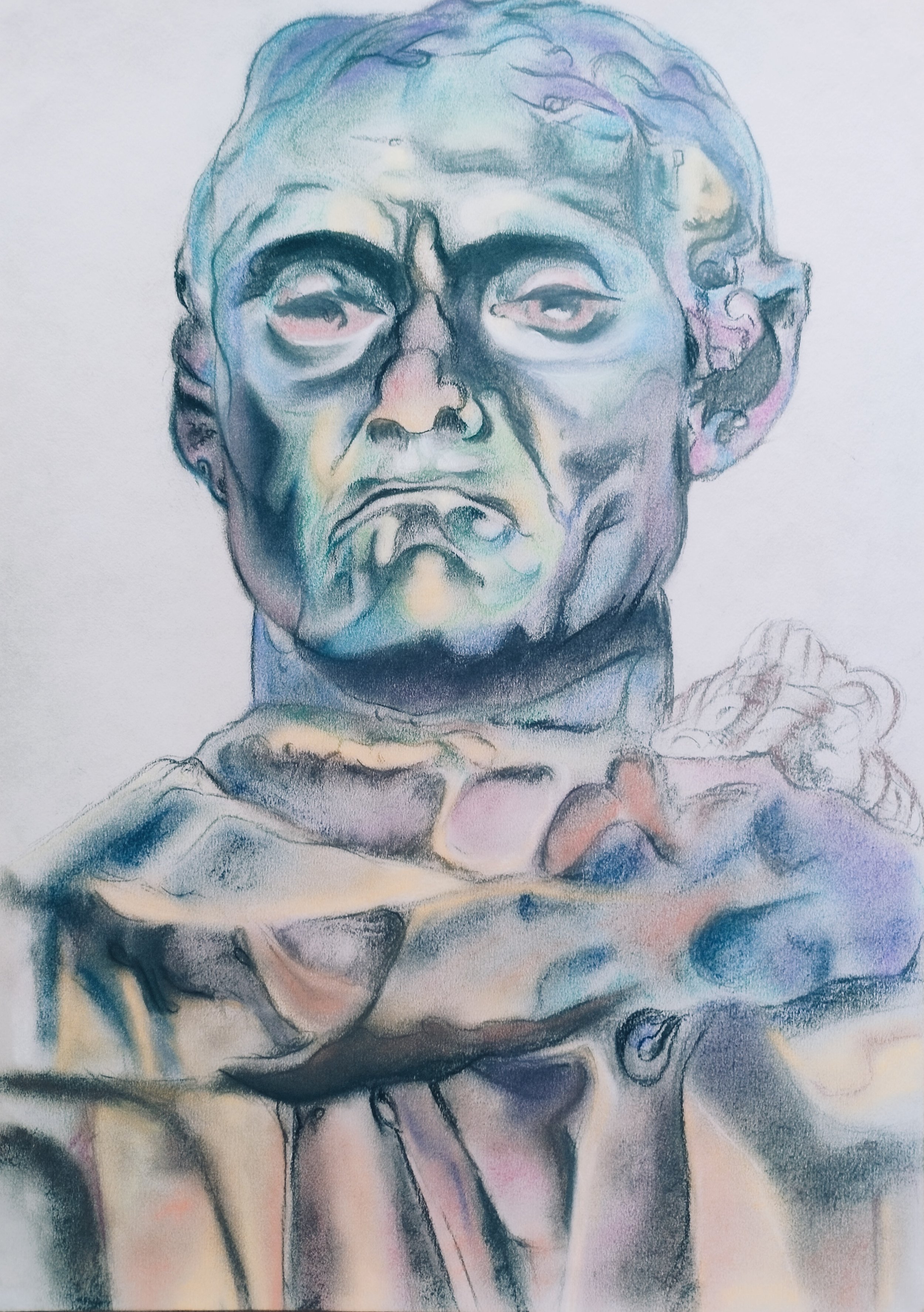

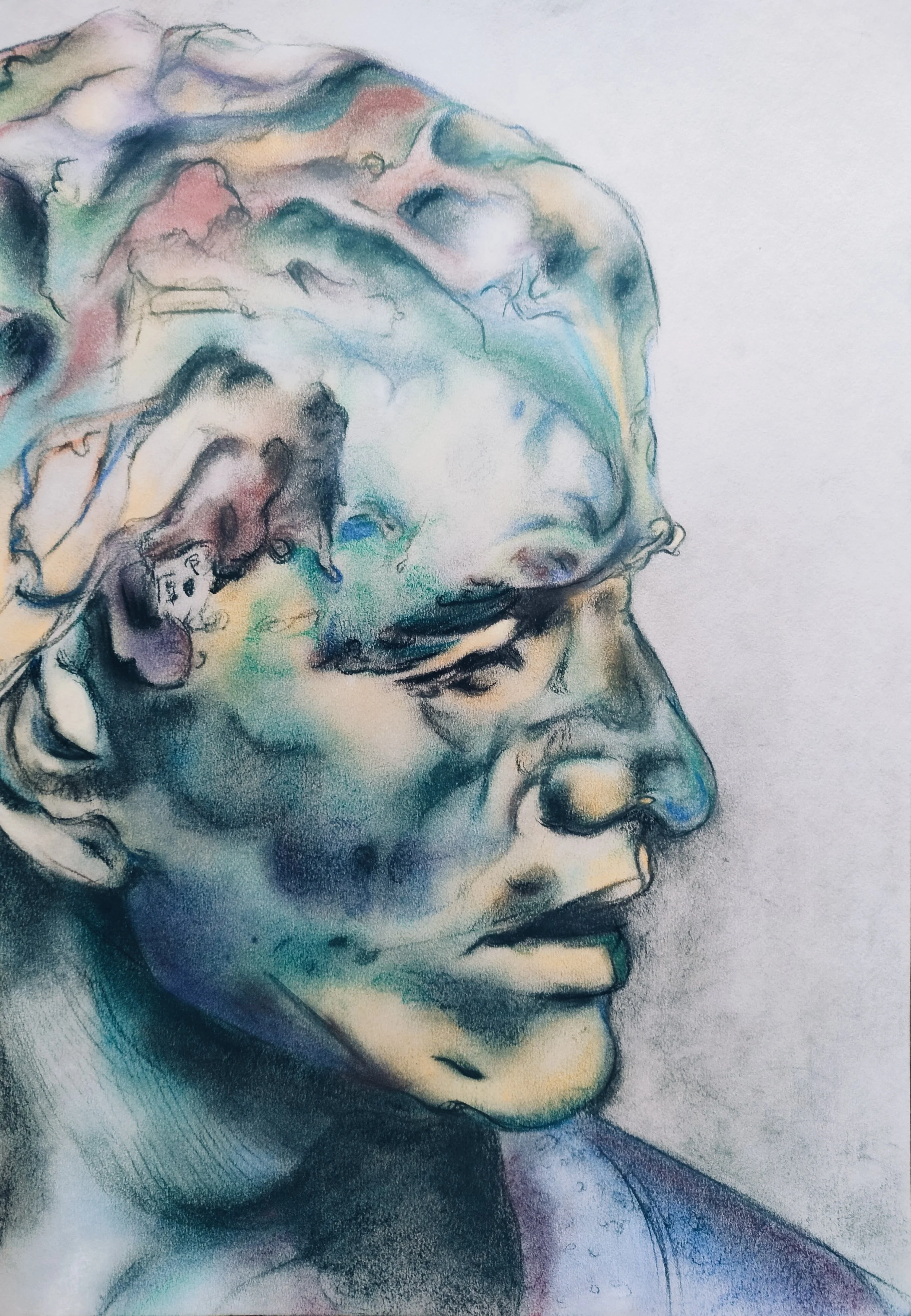

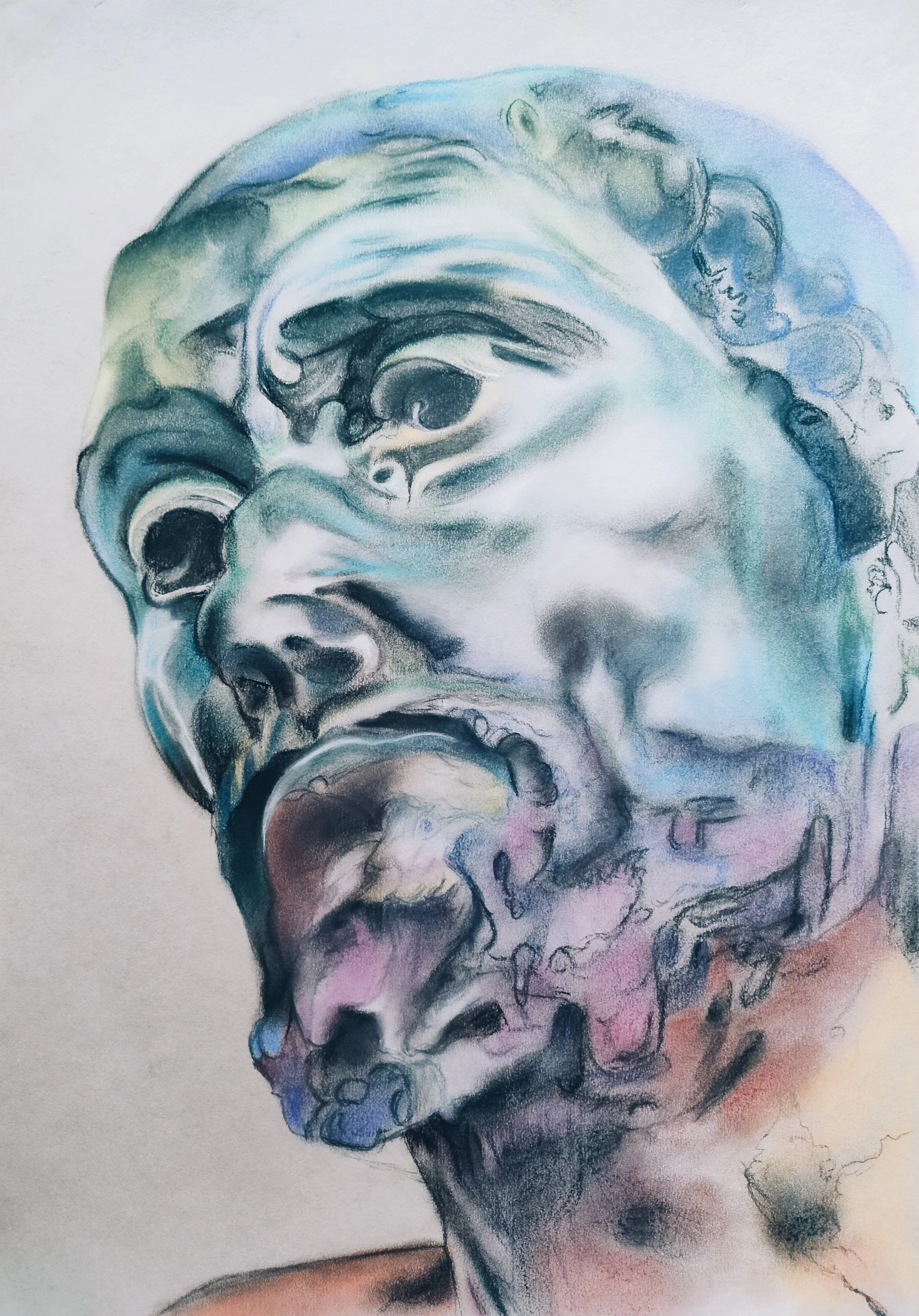

Portraits of courage and despair

Auguste Rodin (1840-1917), the father of modern sculpture, is renowned for breathing life into matter, creating naturalistic, often vigorously modelled sculptures that conveyed intense human emotions. The Burghers of Calais, his best-known public monument, commemorates the heroism of six leading citizens (burghers) of the French city of Calais. In the 14th century, at the beginning of the Hundred Years’ War, they offered their lives in exchange for the lifting of his siege of the city. By portraying their despair and haunted courage in the face of death, Rodin challenged contemporary heroic ideals and conveyed the conflict between the men’s desire to live and the need to save their city.

Entrepreneurs start businesses for the money and the chance to control their own companies, certainly. However, both of these goals are largely incompatible and a source of tension. Giving up more equity to attract cofounders, new hires, and investors builds a more valuable company than parting with less equity. This fundamental tension forces founders to face the “rich” versus “king” trade-offs to maximize either their wealth or their control over the business. Learning to work with this tension between money and power creates an opportunity to come to grips with ghosts from the pasts, the meaning of success in the future, and the messiness of remaining true to the purpose of a venture.

Client

A cofounder of one of India’s most promising startup in the Financial Services and Insurance industry sought coaching to shift the way he was leading and managing growth of the venture.

Externally he wished to develop a stronger presence, and a firmer sense of authority. Within the organization, he wished to get better at decision-making, handling conflict, and managing high-stakes situations.

-

![]()

Step I - Sensing

Introduction

Our client was in one of the most traditional and highly regulated industries in India. Despite a huge potential, industry players had managed to realize only a tiny fraction of that potential. A growing number of companies were trying to create value by streamlining the buying process. Yet, the fact remained that 95% of the products were sold in-person because of its complexity; in-person selling had often been the way. Without expert advisors, consumers were unable to make a decision to purchase.

Seeing an opportunity to truly inspire entrepreneurship amongst the advisors, and through them make a difference to people’s financial security and well-being, three cofounders decided to bring their passion for positively impacting lives with their experiences at one of the country’s first online platform. Together they steadily seeded, nurtured and built a leading-edge innovative platform that created value for the advisors and consumers alike. Instead of using technology to change how people bought the product, they radically challenged how it was sold. That is, instead of cutting out the middleman, they decided to empower them. This progression unfolded at a time when the country was witnessing an unprecedented surge in the creation and funding of startups. 2020 and 2021 saw the highest levels of investment over the previous decade as investment firms, angel investors, venture capitalists, and private equity firms showed confidence in startups.

With the aid of proprietary algorithms and data analytics powering a platform, our client had created one of the company’s most prized asset and a key differentiator in the marketplace. Counteracting India’s low trust market economy by building communities and solving for awareness and trust at an early stage, they had expanded their presence across hundreds of cities and thousands of agents and advisors. By raising funds from leading VCs, the venture had joined a slew of well-funded startups attempting to digitizei of the value chain and bring benefits to a wide variety of participants.

A quest for growth and profitability

As the venture creation and disruption of the industry gained momentum, the business needed to continue to solve for a wide variety of challenges related to product awareness and affordability, distribution and customer experience, trust and simplicity, regulatory challenges and stiff competition, in its quest to for growth and profitability. One of the cofounders, our client, expressed his wish to develop himself through this critical transition by shifting:

the way he carried himself so he could embody stronger presence and greater flexibility

the way he made decisions and handled conflicts in one-on-ones, team, teams of teams, and whole system

the working relationship with his cofounder, and with other senior professionals who were joining/had joined the organization

the management and leadership of the business so he could strengthen the organization and aid in it becoming more "mature."

Putting Founder development into perspective

In thinking about how entrepreneurs lead growth, we employed a life cycle perspective of an innovative new business. Such a perspective included two key phases of entrepreneurial activity:

In the first phase, founders pursued opportunities - in our case, the three cofounders had explored their motivations to becoming an entrepreneur; identified the opportunities they wished to pursue; and experimented to clarify assumptions, reduce uncertainty, and refine the business model.

In the second phase, transitioning to growth - they had been working for the past few years to ensure that their business gained traction in the marketplace, emerged from startup to high growth, and exploited growth options. In this phase, making decisions and taking actions were tied with testing hypotheses and assumptions about the opportunities they were pursuing. Doing so allowed learning, which enabled adaptation and refinement of the venture, and the definition of the next set of experiments and activities needed to perform, and decisions to be made to turn the venture into a sustainable business.

As much as these phases seemed linear and straight, it was important to note that progress through them was anything but. Instead, the key activities and decisions were often interconnected, and the insights gained in one phase prompted refinements in the other. Along the way, sometimes, entrepreneurs discovered fatal flaws in the business model and decided to modify or abandon the venture.

In the case of our client, we noticed that one of the cofounders left in the first phase. And the other two developed a pattern of collaborating and carving out the leadership roles between themselves. It appeared to be one where the other would not cross the boundaries defined between the two. One cofounder took on the role of CEO and became the “boss” and ecosystem builder, and the other the role of innovator, and became the “product guy.” Such a division appeared to have paid off because it allowed the venture to gain tremendous momentum through the years. After several years of leading this venture, multiple rounds of investing and a sizable growth in users and revenues, our client clearly appeared to be in the second phase of leading the innovation life cycle. And the aforementioned development goals were best seen in the context of leading through this phase. Our engagement therefore meant working with the cofounder on his role, including the way he related and organized with his cofounder as they both led through this second phase of the innovation life cycle. Clearly, the roles of the cofounder and the manner of working seemed to reflect the way a fundamental tension - “Founder’s dilemmas,” critical to the “success” of the venture, was being handled. Because growth required raising resources critical to capitalizing on the opportunities, the founders were forced to deal with the dilemmas of either keeping control over the company or building a more valuable company. This is because raising resources called for sacrificing equity to attract executives, non-founding hires, and investors to help build a more valuable company. Such sacrifices had the potential of letting the founders have a more valuable slice as they parted with their equity and gave up control over most decision making. This fundamental tension led to “rich” versus “king” trade-offs. The “rich” option enabled the company to become more valuable but sidelined the founders by potentially taking away prestigious position(s) and control over major decisions. And the “king” choices allowed the founders to retain control of decision making by keeping the position(s) and maintaining control, including over the board, which often resulted in building a less valuable company. One choice wasn’t necessarily better than the other; what the dilemma uncovered was the central purpose of the company and how deeply that purpose was (or not) embedded in its DNA. In our case, the way the two cofounders had divided their roles and span of control reflected their desire for both wealth and power. One cofounder seemed more motivated by wealth than by control. And the other by control as he was more prone to making decisions that enabled him to lead the business and to attract executives who did not threaten his desire to run the company.

-

![]()

Step II - Visioning

Cofounders and their common and uncommon directions

As we began to craft a vision and continued to understand our client and his cofounder, the CEO, we discovered both common and uncommon directions.

On the one hand, the CEO was deeply moved and profoundly excited to lead the firm through multiple transitions from startup to high growth and industry transformation for the next two to three decades, including becoming profitable and taking the company public - “this truly feels like my calling.” And he admitted, most vulnerably, to the importance of his cofounder’s role as the innovator in helping build the platform and the offerings.

Contrastingly, the innovator cofounder was keen on learning and developing himself, growing the business and making it profitable, and creating value for the long-time investors (returning the money) by taking it public. His interests in other dimensions of life and living were important to him, and thus charting a personal and professional journey in alignment with those interests.

The uncommon long-term vision did seem to have a common short- to medium-term goals - continuing to create value for investors by turning the venture profitable and going public.

Going public

Despite all the attention that IPOs receive in the press (and in VCs’ and entrepreneurs’ dreams), we were cognizant of the fact that it was a much less common method of harvesting the value of an enterprise than a sale. Typically, a sale—at least to a strategic buyer—often required an entrepreneur to “give up his baby” and remain in some subordinate capacity for a period of time, answering to some other executive back at the acquirer’s headquarters. This was hardly a situation that most entrepreneurs are able to adapt to very well. The IPO on the other hand, gave the entrepreneur an opportunity to remain captain of the ship, with access to oceans of capital. However, it often brought new challenges and sometimes even greater stresses. Generally speaking, an IPO made the entrepreneur accountable to a new and broader cast of characters. In addition to the board of directors one has been wrangling with the past several years, one’s constituency now includes thousands of shareholders, fund managers, analysts, and the press. Furthermore, whereas the VCs and founders typically focused on the relatively long-term goal of building value, the stock market has an unrelenting focus on quarterly earnings. That is, the audience is no longer a concentrated group of inside investors around the board table, but includes competitors and customers as well. Out of the number of companies that received VC funding, only a fraction ever made it to an IPO. And the reasons were:

Availability of private capital for Indian unicorns - Investors offered not only capital, but also mentorship, network, and global exposure to the startups.

Ill-suited environment - Furthermore, unlike startups in other countries, most of the Indian unicorns had to deal with a regulatory environment that was not as conducive for startups. India did not have a dedicated stock exchange for startups, unlike the US, which had the Nasdaq, or China, which had the STAR Market. The Indian exchanges had stringent listing norms, such as profitability criteria, minimum promoter holding, lock-in periods, and disclosure requirements, that were ill-suited for the growth-oriented and innovation-driven nature of startups.

Scrutiny and accountability - Worse, disclosing financial and operational performance, governance structure, risk factors, and future plans to the public, and complying with the regulatory norms and standards had a high likelihood of exposing vulnerabilities and weaknesses, such as losses, negative cash flows, legal disputes, and competition.

Cost and complexity of going public - The average cost of an IPO in India was higher, compared to the same in the US and in China. Moreover, the IPO process in India involved multiple intermediaries, such as investment bankers, auditors, lawyers, and regulators, and can take up to 12 months to complete. In other words, the financial and legal requirements for a company to go public were onerous.

Despite the numerous difficulties and understandable reluctance, some Indian unicorns were gearing up to go public in the near future, driven by various factors.

Market opportunity and demand for products and services - India had a large and growing consumer base, with over 130 crore people, 70 crore internet users, and 45 crore smartphone users.

Valuation and exit opportunity for the startups and their investors - Going public helps startups achieved a higher valuation, as they gain access to a wider pool of investors and benefit from the market sentiment.

Furthermore, there were a whole set of other economic and societal factors that offered Indian unicorns the opportunity to have a positive impact on the Indian economy and society through the route of the IPO:

Creation of wealth and value for the startups, their investors, employees, and customers by helping investors to exit their investments, earn returns, and reinvest in other startups. And also attracting more investors, both domestic and foreign, to invest in the Indian startup ecosystem, and provide capital, mentorship, and network to the startups.

Increasing of the company’s valuation, and enhancement in brand image and reputation. And also enable the startups to expand their operations, reach, and impact, and serve more customers and markets, both in India and abroad.

Benefiting of employees, who owned shares or stock options in the startups, and the customers, who enjoyed better products and services from the startups.

Stimulation of the startup ecosystem and innovation in India and inspiring and motivating other startups and entrepreneurs to pursue their dreams and ambitions, create more innovative and disruptive solutions for various problems and needs, foster a culture of entrepreneurship and innovation in the country, and encourage more people to start their own ventures or join the startups.

Contribution to the economic growth and social development of India and create more jobs, income, and tax revenue for the Indian economy, and support various sectors and industries. And also address some of the social and environmental challenges and opportunities in India, such as financial inclusion, education, healthcare, and sustainability.

-

![]()

Step III - Organizing

The implications of going public and leading a high-growth business

Our research and experience informed us that, globally, very few entrepreneurial leaders were able to evolve their high-growth businesses through transitions, and the ones that did displayed three key themes:

The skills developed - Founder CEOs deployed a special set of “discovery skills” that were foundational and which helped them through growth and evolution of the firm. In-depth analysis of highly innovative firms revealed five skills that were collectively called discovery skills - they included associating, questioning, observing, experimenting, and networking. Together, they seemed to play a crucial role in an entrepreneur’s ability to transition to growth and becoming large industry leaders. Furthermore, these skills were different from the ones that most executives and CEOs of established firms reported having. There, executives saw themselves facilitating innovation within their organizations. In contrast, founder CEOs used discovery skills to innovate and grow their businesses, spending 50% more time actively engaged in innovation activities than CEOs who were appointed to run established businesses. Indeed, rather than facilitating innovation leadership and work to others, founder CEOs tended to remain actively involved in the innovation activities of the firm—especially those activities considered either highly strategic or critical for building the core capabilities required to execute innovative strategies. Furthermore, and most importantly, when an organization institutionalized these skills in the way everyone made decisions and took action, they had what the researchers called an “innovator’s DNA.”

The roles played by entrepreneurial team members - Instilling discovery skills in the people who surrounded founder CEOs meant that, in practice, entrepreneurship was a collective effort and that it took a high- performing entrepreneurial team to lead high-impact innovation. Studying founder CEOs revealed not only their discovery skills but also their reliance on high-performance teams. This stood in contrast to what has often been imagined about an entrepreneur - a solitary individual toiling away in a lab or garage. The truth, however, was that founder CEOs worked hard to embed the discovery skills in their organizations, enabling even large, complex, established firms to maintain both promoter and trustee roles at all levels. It is this that enabled the innovator’s DNA to become part of the organizational DNA. Research into the dilemmas faced by thousands of entrepreneurs had cautioned us to think carefully about the roles various people played on an entrepreneurial team, in the early stages, and how those roles evolved as an entrepreneurial venture entered the market and transitioned to growth. Specifically, four roles had been identified that founding teams and the teams in innovative high- growth businesses had to be filled. Vertically they were differentiated by leading (transforming) and managing (executing and delivering results). And horizontally they were differentiated by focusing attention on inside or outside the organization. What has been observed was that entrepreneurial teams played all the four roles as they launched and grew sustainable and successful businesses.

Innovation led and execution managed - Founder CEOs focused not just on leading innovation but also on managing disciplined execution. The latter began with executing experiments through which entrepreneurs tested their assumptions. Collectively, this need for both innovation leadership and execution management was seen to not stop once a new venture gained traction with consumers. Instead, these capabilities became embedded in the approach used by teams throughout the company. Thus, both leadership and management skills were central to fulfilling the three key tasks of general management. First - Context setting, which meant scanning the environment to identify external opportunities and threats; making strategic choices; identifying and allocating resources; and focusing attention on projects, targets, and milestones. Second - Executing, which meant defining activities that need to be accomplished and developing and engaging the required talent; designing and aligning organizational structures and processes to enable people within work units and across organizational boundaries to achieve shared goals; and ensuring accountability, monitoring performance, and learning and responding in real time. Third - Delivering, which meant protecting the interests of and creating value for all stakeholders; making tough trade-offs when setting strategy and resolving conflicts; and balancing short-term and long-term priorities.

During the course of our first few conversations with the cofounder and his stakeholders, we tried to gain an understanding of our client’s personal preferences and levels of skills. We did so, first, by employing a self assessment to gauge our client’s preferences on three types of relating - inclusion, control and affect, and correlated them with the levels to which he had developed discovery skills. What became clear were cofounder’s preferences:

control - With a strong inclination for taking charge and making decisions, the cofounder liked to assert his influence in situations. And this preference was juxtaposed by a discomfort with others trying to lead or influence him.

inclusion - The cofounder wished for acknowledgment from others and enjoyed being part of the conversation with others. Yet, at the same time, he was only moderately inclined to include others in his endeavors and interactions, and would rarely initiate going out of his way to involve others.

affect - With hesitancy in expressing emotional warmth and personal closeness with others, the cofounder maintained a degree of emotional distance and did not prioritize deep emotional connections. At the same time, he appreciated warmth from others and wish to surround himself in such environments.

To make sure we had a grounded understanding, we also engaged in a series of conversations with key stakeholders. Those conversations began to paint a picture of:

Journey so far and the way forward - led with strong values and ethics, the venture had achieved a product-market fit and was now in the midst of a shift from growth to profitability through cutting costs, improving efficiencies, and acquiring businesses meant to tap into new opportunities. The venture’s next major goal was an IPO so it could create value for its long-time investors who were seeking to exit, and enable the cofounders to remain captain of the ship and lead the business .

Setting Direction - Stakeholders seemed unclear and spelt a weakness in planning growth strategy, and this weakness was most acute with the leadership team (outside of the cofounders) and in the middle of the organization, where clarity, coordination and empowerment appeared to be suffering.

Executing - Loss of top-performing professionals, as well as hesitancy in resolve and commitment of those who were there, appeared to work in tandem with failure to provide developmental feedback and coaching, recognition, encouragement, and motivation and affect execution. Furthermore, difficulty in delegating the work to others and tendency to micromanage came at the cost of insufficient attention to leadership and management responsibilities necessary in this transition.

Delivering results - Both the cofounders appeared to avoid having the difficult conversations involving facing the truth about keeping loyal comrades, which was leading to compromising performance; letting mistrust fester, giving rise to high levels of control; personal insecurity contribute to detrimental effects on hiring, engaging and building a stronger leadership team; and emotional distance from staff giving rise to shallowness and myopia in outlook across the silos.

Additionally, compromising of personal health and failing to focus on building self for the long haul were showing signs of personal challenges such as feeling of not enough time, feeling of being out of control, and ongoing guilt and burnout.

-

![]()

Step IV - Practicing

Practicing transitioning

All of this demanded thoughtful consideration of what could be leveraged from the venture’s existing:

strategic position (its position in the market and its role in a business network or ecosystem), and

capabilities (operating platform, knowledge assets, talent, organization, leadership, and governance)

the value the business generated in terms of stakeholder relationships and loyalty and cash flow were also to be leveraged to finance growth.

These sources of leverage—combined with intellectual property, products, capabilities and know-how—were proprietary assets that provided strategic advantage while also enabling the business to generate economies of scale and scope. In all, staying true to the purpose, shaping the strategy, and resources and capabilities, while keeping an eye on creating value for investors and stakeholders were pulling the co founder in multiple directions.

The central task was the transition the cofounder needed to make from being a specialist to being a manager and then to leader. He, like any other entrepreneur who wished to lead the growing firm, had to first overcome the challenge of transitioning from an “expert producer” to a “manager/leader.” And one of the key sources of conflict in this transition is the way working as an expert producer - where, a series of well-defined tasks that the expert is confident that he or she can perform, becomes problematic - “what got us here, will not get us there.” An expert producer gains from the benefit of informal power and influence in defining how work will be performed when collaborating with others. However, a manager or leader, is tasked with motivating and mentoring others to perform the work that will influence the manager’s or leader’s success.

To be more precise, the key activities that we initiated to begin the transition, and act to be successful were:

Setting direction by (1) considering long-term goals, mid-term strategies, and short-term objectives, (2) assessing the resources and building capabilities needed to execute strategy and achieve goals and objectives, and (3) attending to the metrics and milestones that will be used to measure progress.

He also began to execute differently and deliver results. The results were allowing comparison with metrics and milestones that were set before execution; the comparisons enabled development of insights that became useful in thinking about the business model.

These insights were uncovering two types of gaps: execution gaps - when the strategic assumptions and direction are confirmed but there is a flaw in execution; strategy gaps - when the strategic assumptions are flawed. On the basis of learning, they were slowly improving the chances of a pivot— refining the strategy and/or refining the capabilities and resources needed to execute the strategy.

All entrepreneurial leaders, including our client, struggled to switch their approach to meet the needs of their growing businesses - or, as the saying goes, sprinters can’t become marathoners. The skills required for growth are learned when leaders are able to jettison habits and skills that have outlived their usefulness and adapt to new challenges along the way. And this can only be achieved when the entrepreneur is willing to take a step back and admit to themselves that their old ways no longer work. By focusing on the very tendencies that had served our client well so far, we began to make slow progress on the four major tendencies:

preserving loyalty to comrades - Blind loyalty becomes a liability in managing a growing, large and complex organization.

task orientation—or focusing on the job at hand - Excessive attention to detail comes at the cost of a large organization carrying on its old way of functioning.

single-mindedness - An important condition for launching a revolutionary product or service, yet the same tunnel vision was becoming an obstacle to being more expansive and examining issues of organization alignment and culture, people and partners, as the company grows.

working in isolation - A must-have for the brilliant scientist with an ingenious idea. However, this burgeoning organization relied on the kindness of customers, regulators, investors, industry observers, reporters, and other strangers, who needed to be attended to.

The cofounder struggled as he attempted to deal with the difficult task of letting go of the old and familiar ways. Like him, letting go gets stymied for all sorts of reasons. But one of the most important one is contending with ghosts from one’s past. The cofounder had developed fundamental attitudes and behaviors of being an “outsider,” which had evolved from the family dynamics of his childhood, later carried into adult life and had now traveled with him into the present— and into the office. Those dynamics had taught him a lot about authority, mastery, and identity. However, they appeared to now be blocking him from fully asserting himself in everyday meetings and other important discussions and engaging proactively on important matters. In other words, when similar issues asserted themselves, he was reverting to familiar patterns of removing or limiting himself - “standing outside.”

The ghosts from the past were not just lurking at the bottom of a sea of memories, but were creating hungers that he had to feed, and they actively steered him in the present as he navigated issues involving shifts in regulatory environment, competitive landscape, strategy to remain relevant, suitability and performance of key personnel, and efficacy of processes and structures. He was bringing these ghosts to life every day through what psychologists call “transference,” a process during which thoughts, feelings, and responses that have been learned in one setting become activated in another.

-

![]()

Step V - Sustaining

Working with the ghosts of the past and the rigidities and vulnerabilities that affect others and the organisation-as-a-whole was a key practice. In other words, experimenting with new behaviours entailed, first, being psychologically present - which is the simultaneous experience of feeling fully and being vulnerable in one’s role. Second, managing anxiety in a non-defensive way and integrating the emotional, intellectual, and physical aspects of the self acts as a key ingredient to being present. Together, this management of inner life was one of the most difficult challenges. Furthermore, accurately gauging how his emotions affect others just as difficult. Through our work together, the co founder was slowly unveiling hidden facets of his leadership, including how his emotional leadership drove the moods and actions of the organization, and then, with equal discipline, to adjust behavior accordingly. The other side of this dynamic was the discovery of how his vulnerabilities were being intensified by followers’ attempts to manipulate. Because leaders, including him, tended to awaken transferential processes—in which people transfer the dynamics of past relationships onto present interactions—among their employees and even in themselves, these processes were presenting themselves in a number of ways, sometimes negatively. Being the ever-reliable, calm, and knowledgeable one was a role the co founder appeared to have been set up to play. Through the power of regular self-observation and self-analysis he was beginning to loosen the grip of this set up.

Concomitantly, the loosening of the grip began shifting the dynamics of the leadership team. This mattered because key to startups surviving as stand-alone firms is materializing growth options through intense and rigorous analysis of strategy, capabilities, and value with an expanded set of role holders. Thinking carefully about the roles various people play on the team was critical to building and evolving the business model shapes the way the venture transitions to growth by focusing on both - leading innovation and managing disciplined execution. Furthermore, such a need does not stop once a new venture gains traction with consumers. Instead, the capabilities have to become embedded in the approach used by teams throughout the company. All of this work at the level of the self, co founder, team, the whole system places intellectual, psychological, social, and even spiritual demands that only a few are able to handle.

Our client had begun employing a powerful combination of honest reflection and consistent action across intrapersonal, interpersonal, groups, inter-groups and inter-organizational domains. This had begun facilitating the thawing of deep-seated mindset and habits that had outlived their usefulness. As the cofounder experimented with new behaviors - with his co founder, his leadership team, and his investors, he began to make small shifts from being a knowledge powerhouse to being an organizational catalyst, from an independent and ‘divide and conquer’ approach within the organization to an interdependent one, from expertise and task-focus to business-model focus, from working in isolation with internal-focus to working the whole organization and the larger ecosystem.