Board energizes Growth

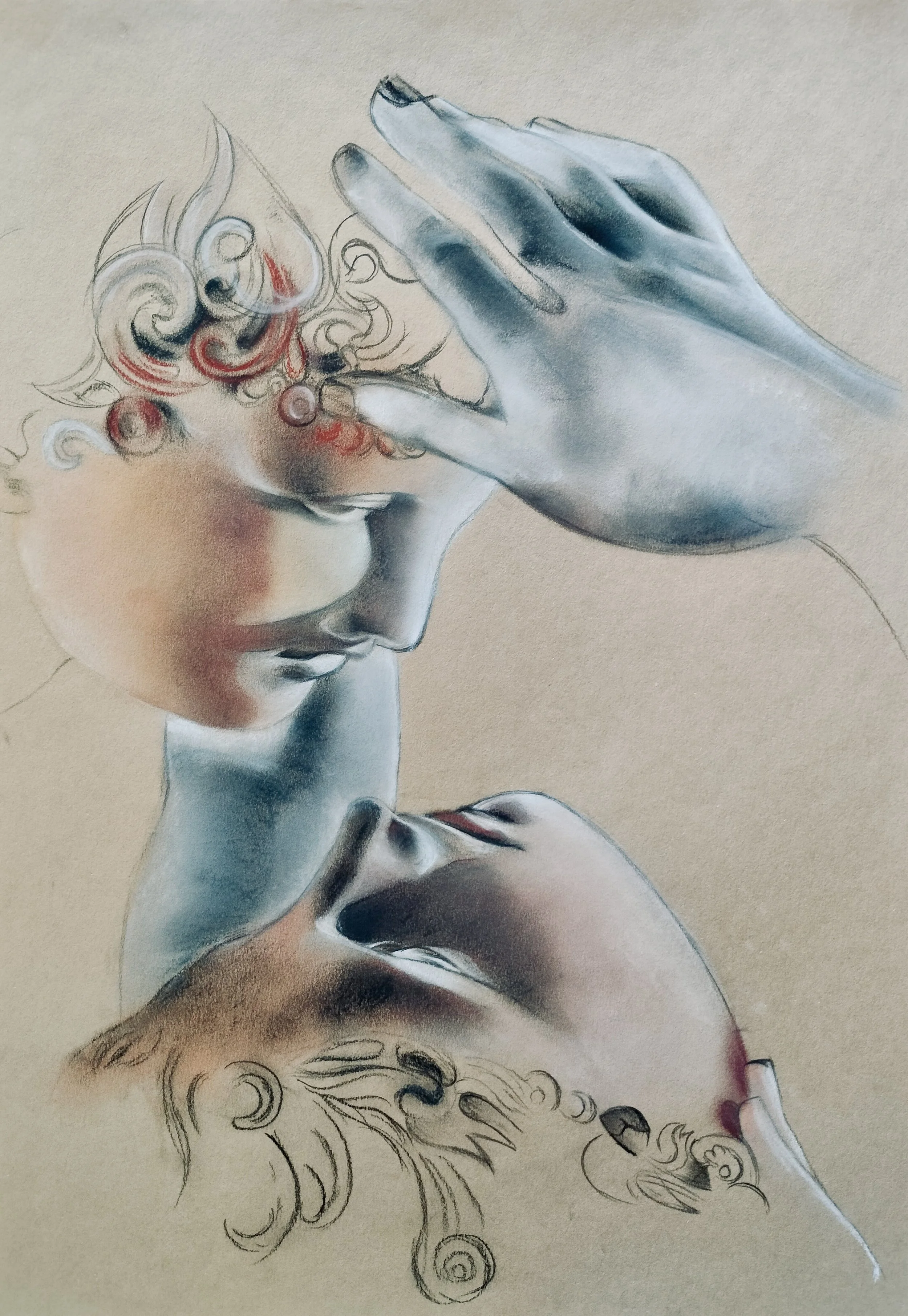

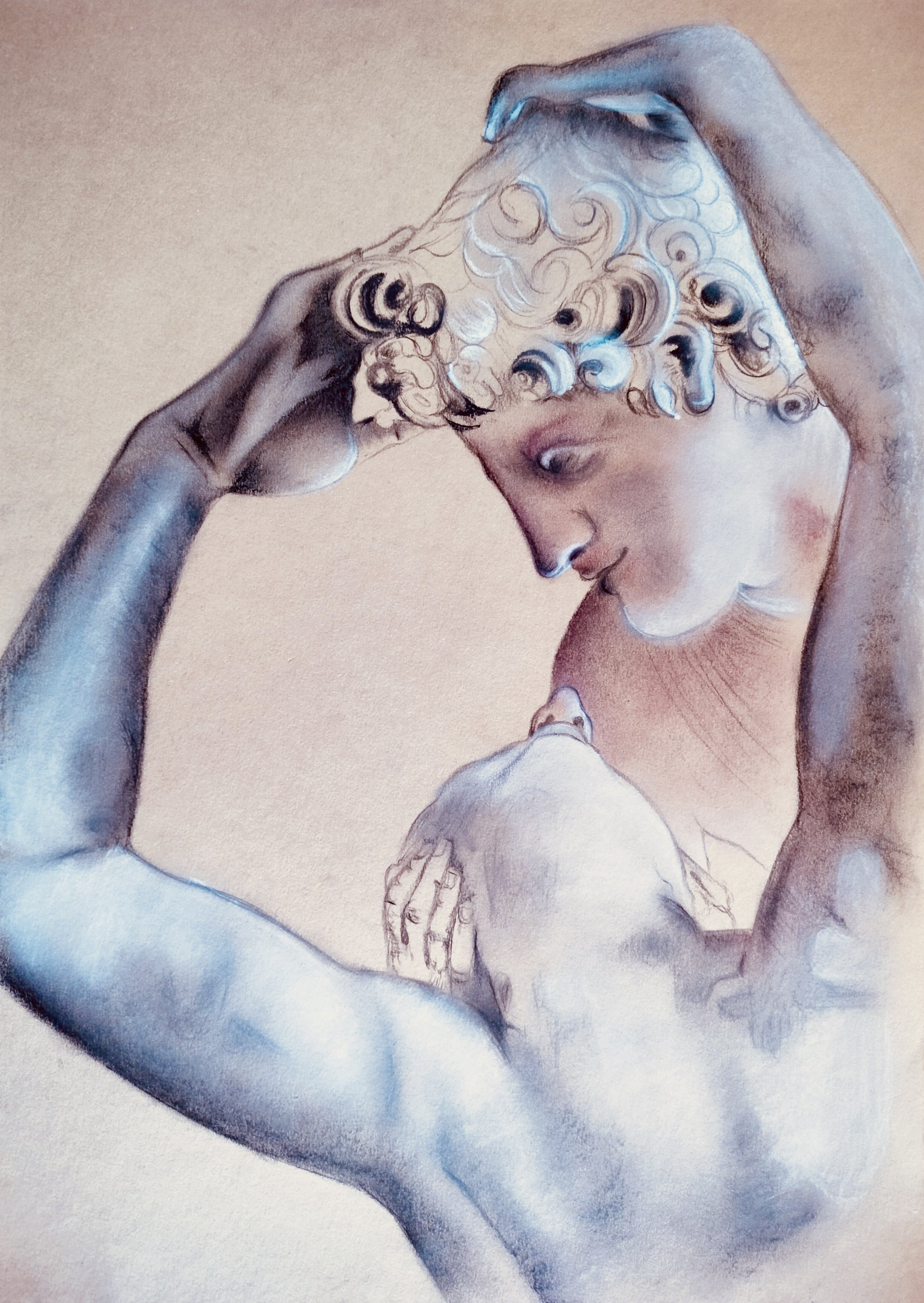

Portrait of revival

Psyche Revived by Cupid’s Kiss is a marble sculpture made between 1787 and 1793 by Antonio Canova. Influenced by his numerous studies of antique art, Canova had developed a unique style, in which his characters expressed refined forms and calm attitudes. In this sculptor he masterfully portrays the loving embrace of two major characters from Greek mythology: Cupid, the son of Aphrodite, and the soul, Psyche, also the most beautiful being in the world. The embrace bares the height of love and tenderness immediately after the lifeless Psyche is awakened with a kiss. Psyche had fallen unconscious after completing the series of tests and trials required of her by Aphrodite to earn the merit of reunion with her son, Eros. Upon completion of the trials, Zeus bestows immortality upon Psyche, and she and Eros are married; their union gives birth to a child named Pleasure. A central message of this myth is that Psyche, the most beautiful being in the world, signifies the beauty of human psyche and the necessary major transformations it must go through in its development.

Governance and management of companies has centered on the idea that management’s objective is, or should be, maximizing value for shareholders. This idea has pervaded the way of thinking in the financial community and much of the business world, and has spread itself across a wide range of topics—from performance measurement and executive compensation to shareholder rights, the role of directors, and corporate responsibility. Furthermore, this thought system has been embraced by institutional investors, managers, lawyers, academics, and even regulators and lawmakers. And its precepts have come to be widely regarded as a model for “good governance.” However, a better model is to have at its core the health of the enterprise (Eros or Cupid) rather than near-term returns to its shareholders (Psyche). Such a model recognizes that corporations are independent entities endowed by law with the potential for indefinite life (immortality). With the right leadership, organizations are to be managed to serve markets and society over long periods of time.

Client

In the midst of a major organization transformation, Board members of one of the world’s leading Impact Investment Fund sought help to shift the way the MD of its Indian subsidiary led his Management Team.

Tensions had developed due to an intense drive for growth and results, leading to series of grievances and calls for return to the core purpose and values central to the organization’s long history.

-

![]()

Step I - Sensing

The presented problem

Our client was a cooperative society offering investment capital for enterprises in developing countries. The Global Head of HR, based out of the HQ in Europe, engaged our studio and presented the problem of a series of grievances against the Managing Director (MD) of the Indian subsidiary.

The MD appeared to leave people behind as he made changes, leading to a negative impact on the overall office morale and staff engagement.

Over the last couple of years, a series of alert calls to various Board members had been made by a female member of the Management Team. She was specifically responsible for capability building of the partners who the Indian unit funded.

The Head of HR sought help to aid the MD in developing the ability and skills in engaging his staff, and leading collaboratively. She emphasized the fact that the cooperative was a values based organisation, and they wished for a culture in the India office where both human values and results were embodied. In our attempt to gain a deeper and broader understanding, we inquired into what got our client to this place:

Historical context - The MD had joined the organization 5 years ago, when the team and (Indian) unit were reeling from a major crisis triggered by microfinance — the provision of debt and other financial services to the poor. It had shaken the very foundations of investment and impact, and caused unprecedented damage to the Indian subsidiary.

The path taken - With a background in banking, the MD had been strongly accustomed to systems and processes and a performance orientation. Once appointed, he gradually hired new staff members and put in place clear procedures and policies meant to drive improved functioning and performance. This was his way of combating poor performance. This approach helped the overall unit in improving performance significantly, albeit solidifying a perception that hiring-one’s-own-team, working long hours and getting ‘it’ done was the way forward.

The actual problem

When we engaged the MD, we were met with a polite willingness and poorly hidden irritation. He asserted that he was being “targeted” despite having delivered outstanding performance. The Head of HR reacted and soon changed her stance with the MD. She clarified that the effort was not meant to target him, and was not driven by a few people “complaining.” Instead, a rising need for a change in the management and leadership approach was necessary to shift the focus of the organization on performance and wellbeing. Very shortly, we were joined by another senior leader based out of the HQ who was a member of the Board of the Indian subsidiary, a member of the larger Board, and also the MD’s boss. He tried to soothe things over with, “The problem is not as bad as it is being portrayed.”

We noticed the manner in which the presented problem between the MD and the MT member had led us to a whole new set of dynamics across the Board, MD and MT. In our view, under pressure, the group displayed signs of falling back on a dysfunctional coping mechanism and working like a pack, that sought ways to alleviate collective anxiety. In doing so, it was unconsciously ascribing an unwanted role to one or more members, consequently leading to skewed interactions. While occasionally straying from a group’s central task was understandable, most problems grow and become significant when a group spends more time in avoidance mode than on the actual work of the group. In other words, the team’s natural defenses sabotage its mission. It is this that prompted us to re-define the presented problem. The challenge now had many stakeholders, and at its heart sat the element that making something profitable often works counter to maximizing positive social impact. The lesson from the history of microfinance had been that scaling financial services for the poor did not necessarily mean that impact too scaled. In fact, the only positive impact, according to a study by Grameen - the bank founded by Muhammad Yunus who pioneered microfinance, was that people who already had higher incomes and established businesses were able to benefit from access to financial services. What was now clear was:

the Board’s lack of attention to the grievance calls and the wish to gloss over the ‘bad’ in relation to outcomes for the partners,

the MD’s quick defense to the concerns being raised, and

a sudden emergence of an organization-wide change in strategy and its execution.

Inquiring into the organization-wide changes (incl. strategy) led to a discovery that the Board had recently launched a new four year Vision & Strategy for the whole organization. First, they wanted to contribute to leading a global movement for social change by becoming a preferred investor and development partner, instead of being just a funder; second, change the focus from executing transactions or projects to catalyzing change; third, place greater focus on specific markets and regions [and let go of others by shutting down offices and operations]. Building a change vision for our work ahead meant empathizing with the challenge that most MDs and Boards deal with in protecting the long-term interest of the firm, its shareholders, and other stakeholders. Meaning the Board was responsible for first and foremost, matters related to strategy and performance, CEO role and succession planning and development. And second, for matters related to oversight of risk and compliance, financial reporting, and corporate citizenship. Yet, like most Boards, our client’s difficulties appeared to be related to over - emphasis on financial performance and insufficient oversight and strategic support for management’s efforts.

-

![]()

Step II - Visioning

Leading Transformation

We decided to continue remaining curious and step in by understanding and advocating on behalf of the total system. An unexpressed set of necessities seemed clear: first, what was the right model for scaling; second, how would the senior leaders build skills and mindset for translating the strategy and executing on the ground; third, how would the subsidiary develop a culture of accountability and performance, balanced by inter-dependence and collaboration; fourth, how would all of this work be underpinned by an environment of trust and respect for cooperative’s values.

To us, this meant building a holding container to deal with the anxiety this change was triggering, including the real possibility that the subsidiary itself may have to let go of staff or be shut down. Building a holding container was necessary to work with:

the dilemmas related to pursuit of scale because it ought to be accompanied by a litmus test to make sure that impact too was being scaled in a way that was both accountable to and transformative for beneficiary communities. And lessons from the history of microfinance, an industry that was at a similar stage 15 years ago were key - the industry achieved financial scale, while impact at scale was largely left behind, and

the way various role holders understood their roles and could take charge to transform it, including the patterns of relating between the MD (as the on-the-ground executive), the Board member (as the go-between but distant Director) and the Head of HR (polarized by the psychological and social aspects, at the cost of overlooking environmental and economic ones) would have to be transformed.

Contextualizing the work of change

The pursuit of scale - identifying and executing strategies, in an international market was no easy task, especially as the Indian market had evolved significantly over the decades and was continuing to do so. Simply going with what one knew was a recipe for falling far short of its goals. Part of the problem was that emerging markets like India had “institutional voids”: that is, they lack specialized intermediaries, regulatory systems, and contract-enforcing methods. These gaps made it difficult for multinationals to succeed in developing nations in the way they would in other markets. Coming up with good strategies was therefore key to realizing purpose. In other words, accounting for vital information about the soft infrastructures by being cognizant of the five contexts was a better approach to understanding institutional variations for our client and its purpose of providing an ethical investment channel and improving the life for a select few in a sustainable way. The five contexts were the country’s:

Political and social systems because they affect its product, labor, and capital markets. Being cognizant of power centers, such as its bureaucracy, media, and civil society, and figuring out if there are checks and balances in place was critical.

Degree of openness because India had been a relatively closed economy due to the lukewarm reception the Indian government gave to multinationals. However, its openness to ideas from the West and people being able to travel freely in and out of the country influenced managers to be are inclined to be market oriented and globally aware.

Product markets because developing countries who have opened up their markets and grown rapidly during the past decade, have companies who still struggle to get reliable information about consumers, especially those with low incomes.

Labor markets because in spite of emerging markets’ large populations, multinationals have trouble recruiting managers and other skilled workers due to the difficulty in ascertaining the quality of talent.

Capital markets because they are remarkable for their lack of sophistication in emerging markets.

Understanding Core Identity

Collectively, this process was seeming like a major shift in the organization’s identity, and leadership and management of its operating model. Because our work entailed helping inspire collective efforts and devising sustainable strategies for the future, we knew we needed an access to the spirit of this organization. We decided to inquire into the organization’s past to gain an understanding and a feel for the energy of its core identity and purpose. This was necessary to help bring forth goals that would resonate and inspire the way forward. Through our research we uncovered that the original idea of this organization had been seeded several decades ago by a call for an ethical investment channel that supported peace and universal solidarity. The founders had a global vision of a just society in which resources were shared sustainably and all people were empowered with the choices they need to create a life of dignity. And the path to realizing this vision was through challenging all to invest responsibly. But more specifically it aimed to provide financial services and support organisations that could improve the quality of life of low-income people or communities in a sustainable way. We summarize the ‘why,’ the ‘how’ and the ‘what’ as below:

Why did the organization exist - to create a society in which resources are shared sustainably and people are empowered to create a life of dignity,

How did it intend to create value - by challenging all to invest responsibly, and more specifically provide financial services,

What did creating value mean - an ethical investment channel for investors and improvement of the quality of life of low-income people or communities in a sustainable way.

-

![]()

Step III - Planning

Engaging strategically

In order to facilitate a more practical and sustainable approach to scaling, the next step was enhanced engagement between the Board Members and the MD was paramount. For this purposes, we conducted a series of interviews with the MD and the MT to understand four key concerns critical to governance through stategy execution:

What were the needs of the customer being targeted, and what was the proposed solution? In the past, the focus had been on limited segments and products, and a personal and intimate experience to their customers (addressed as “partners”). However, they had now entered new segments, devised new products and services, and had developed expertise. A strong push to expand the subsidiary’s portfolio and respond to the changing landscape of the market and customers was afoot. Together, a huge potential for big projects and high-growth was foreseen. And this meant a need for mechanisms to insure scaling impact alongside financial return. These mechanisms could include the three principles suggested by Transform Finance: engaging communities in the design, governance, and ownership of enterprises; ensuring that those running institutions and structuring transactions, add more value than they extract; and balancing risk and return between investors, entrepreneurs, and communities so that everyone benefits. Together, a far more facilitative approach and designing of customized solutions, clear values-based decision-making on specific metrics, and a shift to mitigation of risks was obvious.

Who were the competitors and how did they compete against them? For long, the cooperative had been seen as an internationally reputed lender. A shift to becoming an investor of choice and partnering in building capacity was now being called for. Fundamentally, it meant letting go of being a “social organization,” and taking on more risks to deepen social impact in a sustainable manner. Furthermore, to continue to compete in the marketplace, customized solutions, partnering with other firms who were better regulated, accelerated execution, scaling of impact and reduction in project time were critical. Most of the long-term organizational members had been there because they made a real difference to the lives of others. To them the organization facilitated an opportunity to play a bigger role in making a difference to society. The culture of flexibility and collaboration had allowed them to grow and dedicate themselves to making the organisation successful. Over time, new set of tools for analysis had helped improve risk management. Also, greater autonomy, because tasks and project approvals were being conducted locally instead of the HQ, had improved the local subsidiary. Most notably, members felt that HQ placed greater trust and confidence in the members of the subsidiary, and this was important as it propelled them “stretch.”

What did they need to do to make their strategy profitable and impactful? The culture within the organization had been family-like, with limited concern for risks. For the last few years, drive for short-term growth and bigger deals began putting intense pressure, transforming it to a reactive one - i.e., reacting to problems instead of proactively striving for excellence. Anxiety and disturbance related to who the competition was - “the big banks or other social impact investment players?!” only exacerbated the pressure. Blaming became the norm - “I am ok. you are not,” emotional volatility common, and feeling like one was “walking on egg shells” most of the times. Furthermore, role definitions did not matter, and neither was power to make decisions and have a “say” present. Worse, this fragmentation spilled over and turned into a “we” vs. “they” divide between the Indian subsidiary and the HQ. The sub-optimal allocation of tasks between the two offices was leading to a negative impact on response to customers - some of the subsidiary’s experiences with partners were turning moments of delight into moments of embarrassment. A gap between espoused and practiced values, and insufficient value addition and impact creation were tearing the organization. The staff’s capability and competency, perceived to be the core engine of the organisation, lacked adequate development and appeared to be bursting at the seams. And all of these difficulties called for a change in the model.

What was the game plan for sustaining competitive advantage or for strategic renewal? The way forward required a multi-pronged approach - first and foremost, re-evaluating assessment and feedback processes so they shifted from success/failure paradigm that focused on celebration/criticism o inquire/discover thot focused on pursuit of value-generation. This was especially true in the employment of financial metrics and ESG as a way to work with the dilemmas that scaling surfaced. ESG ratings, intended to provide information to market participants (investors, analysts, and corporate managers) about the relation between corporations and non-investor stakeholders interests, needed to be better understood as a primary metric. Increasingly, ESG ratings providers had come under scrutiny over concerns of the reliability of their assessments because the ratings, intended to measure “ESG quality,” were problematic because quality itself did not have a single agreed-upon definition. Second, the re-definition of roles and responsibilities to cope with new tasks and inter-dependencies. This included, securing, managing and monitoring of various projects through deployment of new technology and partnering with experts at the local level. Third, re-focusing by altering the inadequate attention to processes and discipline, both key to building capacity and capability necessary for sustainable growth. Fourth, re-shaping of the fear-based environment to a psychologically safe one, where “personal” conversations in group meetings would improve employee engagement while sustaining above-average financial results. This also meant creating new organizing mechanisms so functional teams could discuss goals, expectations and work progress. Furthermore, offering organized mentorship and support for new employees to reduce the sense of loneliness and isolation that would overwhelm them.

-

![]()

Step IV - Practicing

Developing deep capability

We proposed working with two specific domains of development because the journey had implications for the Board, the MD and the MT:

1. Personal Development at the intra-personal level - examining one’s own identity (“Who am I?”) and one’s propensity to play a certain life-role

2. Role Development at the group-level - examining one’s organizational role and one’s propensity to stray from one’s central task of managing conflicting tensions in a group or system.

Writing one’s life story and employing the Existential Universe Mapper became our starting point for the above two. Life story because leaders, consciously and subconsciously, constantly test themselves through real-world experiences and reframe their life stories to understand who they are at their core. And the Existential Universe Mapper (EUM) because it helped understand preferences for different levels of existence, wherein each level was a composite value system of needs, wants, attitudes, beliefs, values, and proclivities that were specific and consistent with internal/external conditions corresponding to that level. Following are some of the major themes:

A high preference for relating with the world in an orderly fashion, and a high preference for striving towards higher levels of achievement by forging mutually beneficial links with others. The combination of the two meant that members understood the ways of the system and leveraged its opportunities for achieving one’s goals. They blended continuity with change and worked towards continuous improvement. Because of emphasis on rational pragmatism, difficulty in dealing with intangibles was likely. Another manifestation of this preference was that members had considerable facility in dealing with people they shied away from intimacy and close emotional encounters, and found it difficult to question “basic assumptions” and make paradigm shifts.

A high preference for belonging to a safe haven and a low preference for fulfillment of one’s desires. This combination meant that members had a strong commitment to their systems of belonging. Their overvalued virtues of selflessness, modesty, obedience, acceptance, etc. tended to dislocate direct aggression. They were prone to being passive aggressive, and were experienced by others as easy to get along with. However, they ran the risk of being ignored, found it difficult to demand their due and were prone to sulking/withdrawal if denied. They likely rationalized their lack of agency as faith/concern for the system, projected their disowned ego needs on to other people, and found it difficult to deal with unknown and unfamiliar.

Finally, a moderate preference for wishing for and working towards a utopian world where everyone could live in peace and harmony.

Creating space for dilemmas and fears

Following this awareness, we worked with the MD and MT in two separate ways

First - holding alignment meetings between each member of the MT and the MD to create, design and experiment with leadership initiatives key to improving the organization-at-large, relationships with key stakeholders, functioning of teams and self leadership.

Two - individualized coaching sessions to support the work above, by going deeper and aiding in perceiving, thinking and communicating differently. Together, they were critical to experimenting with new behaviors meant to overcome individuals’ immunity to change. This process was meant to challenge psychological foundations through inquiry into beliefs long held close, perhaps since childhood. And it required people to face and admit to painful, even embarrassing feelings that they would not ordinarily disclose to others or even to themselves. Indeed, the MD himself opted not to disrupt his immunity to change, choosing instead to continue his fruitless struggle against his competing commitment to being right, feeling competent and not being blamed or feeling ashamed.

We brought the two together in small group sessions where we worked with the MD and the MT on the collective initiatives for change. The group identified a series of initiatives, the fears or worries and the beliefs that obstructed making progress:

Leadership Initiatives -The pursuit of development of people (mindset and skills for future) in a way that they could achieve a better balance between the subjective (feelings and emotions) and the objective (performance, tasks, logic), which in turn will help them engage in difficult conversations and shape a new identity (combining social and financial)

Big Assumptions in the way of making progress - The development of people will lead us into difficult situations that will jeopardize business performance, staff functioning, and our self image as a “humane” org. Such a break down will worsen team spirit, “sink the ship,” make the roles irrelevant, make people fall sick and completely tarnish the image of the organization in the marketplace. The end result will be a mediocre combination of social and financial, and collectively ensure that they are “doomed.”

Testing assumptions by experimenting with new behaviors - Over a period of 6 months and with support of a series of coaching sessions, each LT member had begun to be more at ease with self and their individual leadership initiatives. They became more assertive and had greater self belief. The level of stress and burnout reduced dramatically and they became more transparent and vulnerable - disclosing more than they ever had in the past. They also became more open to others and listening improved significantly leading to increase in trust and collaboration.

-

![]()

Step V - Sustaining

A key dimension to sustaining the journey was the work with the MD and other members of the Board to improve their partnership - governance as is hadn’t been working well. Experimentation with more frequent visits and a dialogue between the two had begun as evidenced by:

Appreciation and engagement with the MD’s entrepreneurial boldness and process discipline, both central to reviving the subsidiary from dire straits and transforming it into a force to reckon with in the Indian ecosystem.

Understanding the workings of the subsidiary and staying abreast of the industry developments, without getting too involved or controlling because the Indian subsidiary was operating in a context quite different from other markets, including the HQ.

Recognizing the need for diversity, a key ingredient to expanded perspectives and specialized knowledge, as necessary to help deal with the short-term blips, investigations, media and brand positioning, digital transformation, and other situations that the MD faced.

Energetic debate, necessary for important decisions that emerge out of intelligent stress-testing, and finding a new balance between “getting along” and conflict avoidance on one hand and needless aggression and strong opinions on the other.

Engagement with the inherently fraught process of succession, the most visible and high impact responsibility of the Board, by investing in exploring MD’s future direction and succession plans and begin looking externally in the event that the MD decides to leave.

To sustain the journey, we worked closely with the MD and the Board on defining and highlighting the MD’s leadership initiatives, despite his resistance and hesitancy:

First and foremost, building a management team - We discovered that the top key challenge of having a MT that he was comfortable with and was apt for the organization, consisted of three elements: external recruiting, internal leadership development and retention. First - external recruiting, a common problem for enteprise leaders, was harder for him as a social enterprise leaders, because of the weakness of human resources (HR) function. Hence, apart from the skills and knowledge needed for a particular position, three dimensions of suitability were important for him to consider for high-responsibility positions: Social mission fit, Cultural fit and Founder/Leader fit. Second - internal leadership development was the way forward to help solve many of the potential problems of outside recruiting. This meant promoting of existing staff into senior leadership positions, which would also provide the additional benefit of offering rewarding career opportunities to employees. However, none of this was going to happen without a strong conscious effort, some skills and knowledge, and an investment of time, energy and money. Third - retention for social enterprises like our client, was of critical importance as it was often hard to replace staff with outside candidates who fit well. Team members who had successfully been socialized and were familiar with its specific business model were therefore key assets of the organization. At the same time, the fact remained that most social enterprises tended to “hire young” due to lower salary expectations of less experienced employees and greater adaptability to the organization. And especially talented and ambitious staff who sought to broaden their experience and take over responsibility would often be lost or become disconnected and de-energized in the absence of interesting career and development prospects within the organization. While our client’s organization had been growing fast, new leadership positions had not translated into promotion opportunities since active internal leadership development had been long neglected.

Second, delegating and planning for succession - We were cognizant that this consisted of two related aspects, delegation and succession. And here, with our client, succession was more challenging than delegation, as it often was from the perspective of the social enterprise leaders. In our experience with delegating, we discovered two challenges with delegation. One was a suitable candidate or team to fill the founder’s/leader’s shoes – in parts or fully, temporarily or permanently. And the second, a far more critical factor was the MD’s own attitude and ability to let go. Feeling disappointed and frustrated with way the engagement was proceeding, the MD began to express the possibility of leaving and pulling out of the operations of the organization. He could take up an advisory role on the board, or embark on a new venture or different career path. Hence, a need to become prepared for an unexpected emergency – including the MD falling seriously sick or having an accident and being temporarily out of the office, or even worse. It wasn’t lost on the organization that the organization had faced a succession problem in the past - the previous MD had died quite suddenly, leaving a huge vaccuum and a deep sense of loss.

Third, balancing and integrating - Balancing conflicting demands from the often manifold roles and aligning the daily work with actual strengths and preferences to ensure highest effectiveness as well as motivation was one face of the third element. The other face was that of integrating differing, and often conflicting stakeholder interests inside and outside of the organization. The first one, balancing, was a major element because most social enterprise leaders, including the MD, went far beyond the call of duty to achieve the organizational mission. Furthermore, he, like most, was also a relentless advocate for the cause on any suitable occasion so it could achieve broader systemic change. The second one, integrating conflicting perspectives, acted as a complement because addressing the pressing needs of specific societal groups and often partnering with other institutions serving a similar purpose, leaders like himself were accountable to a diverse range of external stakeholders.

Developing personally and professionally - Development was first and foremost about self-leadership and self-development. Advocating for both technical and management skills, we emphasized that for the organization to succeed, great clarity of mind and high awareness for complex realities were central to crafting trailblazing strategies. Striking the right balance between showing pathways forward while empowering team members would be key to execution. Furthermore, in this field of helping others and solving social problems, strong personal ethics were needed to lead social enterprises, like our client’s.